A number of our friends have been asking what type of sailboat we'll be picking for life upon the water. Just start looking at YachtWorld or SailboatListings and you'll soon see that perusing the 28,000 odd sailboats listed between them is no small feat. If you scour the web you'd probably find another 30,000 sailboats for sale and then there are local listings to consider. With all these options how are we going to narrow things down to a managable list?

After much research and consideration we've used the KISS-principle to settle on a short list of requirements for our future home and vessel. Much has already been written on this topic so we won't try and duplicate it all here. In no particular order the requirements we've come up with are:

- Has been well taken care of and is "cruise ready"

- Fiberglass mono-hulled Bermuda cutter

- No shorter than 32' and no longer than 38'

- Hanked on headsails and slab reefing on the main

- Has a tiller attached directly to the top of the rudder

- Full keel or modified (cut-away) keel

Beyond this list nearly everything else can be modified or adjusted as needed. Sure, there are a few things we'd like to see like a water maker, solar & wind power, composting toilet and as little teak as possible on the topside, but we're preparing ourselves for a boat that might need some amount of work to bring it to what we want in a world-capable cruiser and so beyond the six requirements above we aren't as concerned with other issues that we have deemed "nice to have."

As it turns out, this small list of requirements is enough to narrow down the list of suitable makes of sailboat to something more manageable.

Let's take a closer look at the requirements above and why we're making those choices.

Has been well taken care of and is "cruise ready"

While we understand that every boat is going to need a certain amount of work to get it ready to cruise we're not looking for a "project boat." We'll save money by doing as much maintenance as we can ourselves but we don't want to get into a project that takes several years to complete. In fact, if the boat isn't suitable for living aboard immediately after purchase or we think that it's going to take more than a year and a half to be totally cruise-ready then we'll skip it.

We're basing this decision on the horror stories and multi-year refits that we've read about and watched on YouTube. Frankly we'd rather be sailing and anything that takes us away from that has to be weighed carefully.

Fibreglass mono-hulled Bermuda cutter

We'll want a hull made of fiberglass versus wood or metal for a few reasons. It is the least maintenance-intensive material for cruising boats and repair is relatively straightforward. We'll probably skip a cored hull due to the complications that come with older boats that are built with balsa or foam in hull as it's difficult to inspect and may present costly structural problems down the line. Both wood and metal hulls have their advantages but the cost and time involved in keeping a wood boat or the specialized equipment necessary to maintain metal make these less than attractive options for us.

A monohull simply means that we're looking at a traditional sailboat and not a catamaran or other type of vessel.

Bermuda cutter rigged boats are a singled masted vessel with more than one headsail in addition to the main carried by both a sloop and cutter. We prefer a cutter to a sloop because it means that we have a more manageable sailplan (more options for dealing with weather) and the sails are generally smaller and easier to manage.

Here is a classic 28' Bristol Channel Cutter. Note the two sails forward of the mast - that's what makes this a cutter. A sloop would only have one sail forward.

We considered a ketch (two masts) however we were dissuaded having learned of the difficulties of using a wind-vane on a ketch not unlike the length of vessel we are looking at (see Robin Knox-Johnston's book A World Of My Own). Also, we spent a week aboard one in the the BC Gulf Islands last year and from that experience we found that we don't particularly care for the added complexity of another mast and in the case of most 30-32' vessels, having a boom directly overhead the aft cockpit. Tammy is mildly vertically challenged and this configuration is difficult for her to work with.

No shorter than 32' and no longer than 38'

Vessel length is a contentious topic. Many people feel strongly about vessels of a certain length since it directly affects such things as top cruising speed, general seaworthiness, usable deck and cabin space, initial purchase price, maintenance time-requirements and related costs.

Admittedly we've been influenced by what Lin and Larry Pardey have written about boat length in Cost Conscious Cruiser and their mantra Go Small, Go Simple, Go Now. The fact is that Tammy and I are extremely good at living together in small places and, coupled with the fact that we're doing this on a limited budget, we need to be responsible with our money and plan accordingly for future maintenance costs and time. Lin and Larry did a very good job of breaking down the time requirements for maintenance in a given year (assuming nothing critical happens) and from their experience, the bigger the boat the more time you'll spend maintaining it and therefore the less time you'll have to sail. As we've already said, we want to spend more time sailing so smaller is probably a better option.

While boats smaller than 32' have made many successful circumnavigations, most have very cramped living quarters and therefore no room for additional crew. We very much wish to be able to accommodate at least another couple, perhaps three visitors at a time and so anything below 32' is pretty much a non-starter. 38' is on the upper-end of our preferred vessel length but we have gone so far as to allow it simply because it gives us a couple more options to chose from.

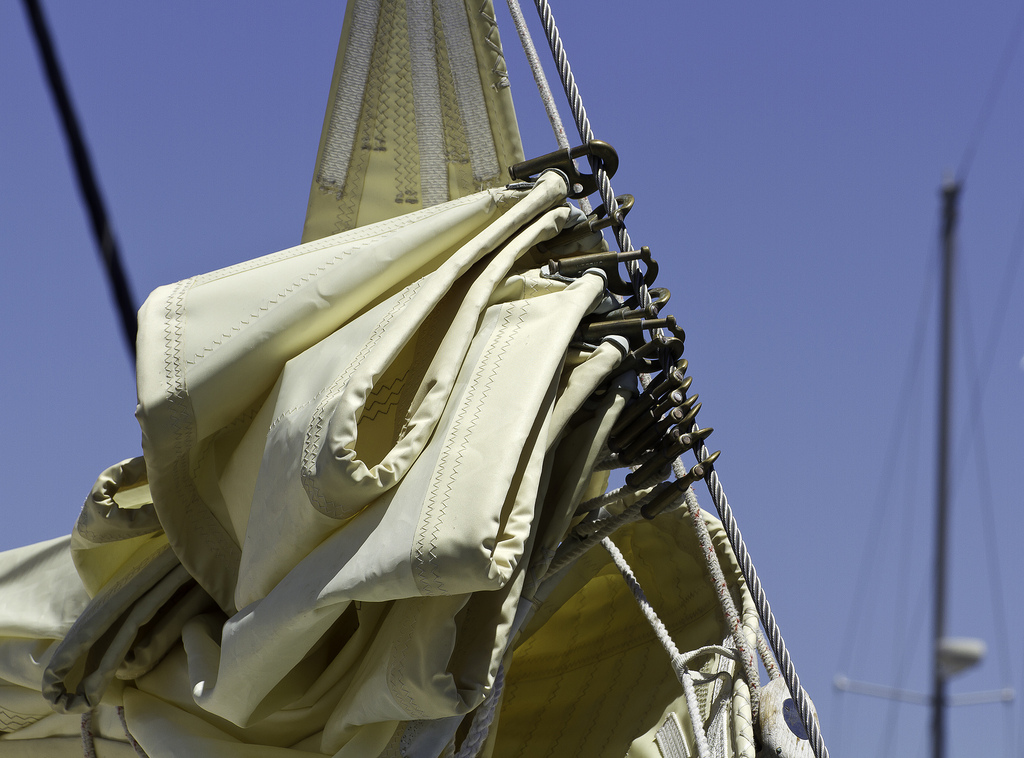

Hanked on headsails and slab reefing on the main

Hanked on headsails and slab reefing on the mainsail affect how sails are "attached" to the boat, how they're taken up and down and reefed as needed.

From Wikipedia: "Reefing is the means of reducing the area of a sail usually by folding or rolling one edge of the canvas in on itself. The converse operation, removing the reef, is called "shaking it out." Reefing improves the performance of sailing vessels in strong winds, and is the primary safety precaution in rough weather. Reefing sails improves vessel stability and minimizes the risk of damage to the sail or other gear. Proper skills in and equipment for reefing are crucial to averting the dangers of capsizing or broaching in heavy weather."

More "modern" sail handling options include roller furling on headsails and boom or mast furling on the mainsail. While they have their advantages over simpler hanked-on solutions, we're following the KISS-principle here and opting for hanked-on headsails and slab reefing on the main.

Here's our thinking: furling is convenient for coastal cruising but we are planning to use the trade winds to travel and eventually visit remote islands where replacement parts are non-existent. We want sail systems that won't breakdown and screw us when we need them the most. Roller furling is magnitudes more complicated than a hanked-on solution and the thought of having our mainsail depend on equally complicated boom furling or getting caught-up in the mast gives us the willies.

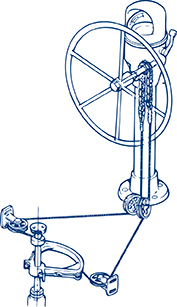

Has a tiller attached directly to the top of the rudder

In a time when steering wheels are ubiquitous on sailing vessels over 30' a tiller appears antiquated and out-of-place. Although they were the go-to choice of steering for hundreds of years, they have fallen out of vogue in the past fifty years as sailing has become more commonplace. The reasons are obvious: wheels are easy to use - the boat goes in the same direction as the wheel; they are particularly useful on craft larger than 40' where the required tiller length begins to become less viable; and perhaps less important, they look "salty" in the eyes of many.

For vessels under 40' and certainly those closer to 30' tillers remain the best and simplest option for steering a boat, and for us, a requirement for blue water cruising.

The advantages of a tiller are many: short of breaking, there are few reasons for one to stop working as they rely on very minimal working parts. This is in sharp contrast to a wheel-based system that requires many cables, pulleys and gearing pieces (or worse yet, hydraulics that mask the "feel" of the boat's balance) where there are exponentially greater number of things to go wrong. Tillers are far cheaper to replace, the associated electric/hydraulic auto-pilot systems are simpler and therfore less expensive and it is easy to rig sheet-to-tiller and windvane steering.

As an added bonus, tillers can be held in place between your legs thereby freeing your hands for more important duties such as trimming sails. People who have sailed dinghies will understand the usefulness of being able to extend a tiller with a hiking stick and appreciate added flexibility while docking and under way. We also look forward to being able to remove the tiller while at anchor: this makes the vessel harder to steal and increases room while entertaining guests. Try doing that with a wheel pulpit!

Whatever boat that we buy will have its tiller mounted directly to a large, barn-door like rudder as opposed to a through-hull rudder post. This reduces the number of holes passing through our hull as well as making all steering connections accessible and easily inspected.

Full keel or modified (cut-away) keel

Like the steering wheel, fin-keeled sailing boats are common place. They are often faster and more nimble than their heavier full-keeled cousins and in some cases, have shallower draft making them ideal for certain locations. If we were looking for a boat for coastal cruising they would be an option but for us, a full or modified/cut-away keel is the way to go.

Notice how the fin projects and leaves the prop and spade rudder relatively unprotected.

Full keels are really "part of the boat" and typically contain encapsulated ballast - that's the bit that helps the boat stay upright and recover from being knocked-down. As they are part of the boat they aren't susceptible to problems associated with keels that are attached to the boat through a series of bolts and if you ground the boat - something every sailor does eventually - they will typically weather better than a more fragile fin.

Full keels and their modified cousins have other advantages: they protect the rudder and prop from damage and fouled lines. Also, because the keel extends from bow to stern, these boats tend to track well & stay on course when running in trade winds. Heavy full-keeled boats generally perform well when the weather turns nasty and come into their own when the wind picks up.

Unfortunately you can't have it all: a full keel means more surface area in the water and an overall slower boat. As mentioned, they are not as nimble as their fin-equipped cousins and often require a greater turning radius.

If repairs are needed or bottom paint needs to be re-applied, full keeled vessels are somewhat easier to tie up along pylons to await a departing tide or laid down on a sandy beach if haul-out options are limited.

For us the option is clear: we are going to be cruising long-term so speed isn't as important as relative comfort when the going gets tough. Also, we appreciate the ability to track well and take a grounding better than a fin. That said, we'll do our very best to stay away from the rocks!

And Sailboats?

In our next article on this topic we'll review the few makes of sailboat that meet our requirements. Stay tuned!